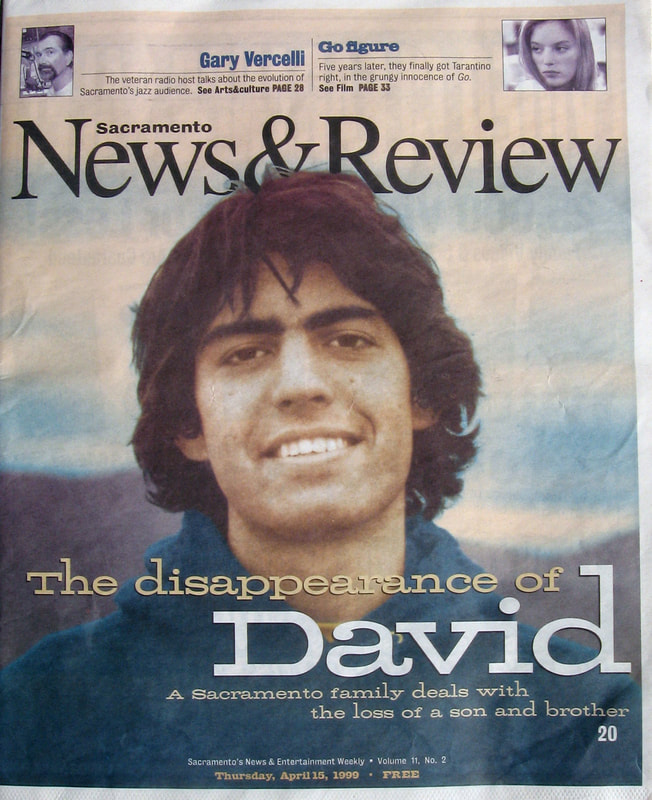

A Sacramento family deals with the loss of a son and brotherSometime after dawn on the morning of April 7, 1988, a 24-year-old man named David Orr slipped out of an unlocked door of the Anne Sippi Clinic in Los Angeles, where he was a resident. David Orr disappeared that morning never to be seen again. This wasn't the sensational kind of disappearance that draws television cameras and public interest. There was no exhaustive FBI investigation for material clues leading to his whereabouts. In this case, the only people left to wonder and worry about the absence were family members, most of whom now live in Sacramento. David's life had been a helix of contradictions for some time.Though officially considered a danger to himself, David had often shown the capacity to be singularly charming, bright and resourceful. He didn't finish high school, for example, but the day after his classmates at Wooster High outside of Reno graduated, David rode his bicycle 10 miles into town and breezed through the GED. Another time, just two years before his disappearance, David marshaled the substantial physical and mental stamina necessary to complete a grueling mountain climb to the top of Argentina's Mt. Aconcagua, the highest peak (22,835 feet) in the western hemisphere. But everyday living became a trial for David and he was diagnosed as mentally ill by the time he was in his 20s. Eventually, he became a resident at the Anne Sippi Clinic, a private mental health facility, which fits inconspicuously into the hills of El Sereno, a Latino working-class neighborhood in southeast Los Angeles. Attendants were on duty around the clock at the clinic that day in 1988 when David disappeared. But it wouldn't have been difficult to slip out of a door while they were on the other side of the building. That's what David must have done. And he disappeared without a trace.Over the next 10 years, David's family did what any family might in a similar situation. They searched endlessly for him, contacting police, hospitals and mental health agencies all over the country. They hired private investigators. Their hopes grew slimmer as time passed, but some in the family remained optimistic that David might turn up again one day. Then in February 1998, Sacramentan Susan Orr saw a picture of a man who resembled her son in a Bodega Bay newspaper. She called the missing persons unit of the Los Angeles Police Department, something she had done regularly -- each March 21 -- on David's birthday. The very next morning a woman from the LA County Coroner's office called. The investigator told Susan that her "missing" son of 10 years was, in fact, dead and that David's body had actually been identified seven years earlier, back in 1991. The identification was made on records of a body found at the railroad tracks near Valley Boulevard in the City of Industry. David's body had been discovered around 1:30 p.m. on April 7, 1988 -- about eight hours and 22 miles from where he disappeared. David had died on the very day he had disappeared.Since coroners could not then identify the body, David was buried as "John Doe #93." When he was identified several years later, the Orr family, inexplicably, was not notified. The following is an attempt, on the 11th anniversary of the disappearance of David Orr, to solve at least part of the mystery of his life and create a context for understanding why his death came -- for him and his family -- in the disturbing way it did.

|

By Marcus CrowderFrom Sacramento News & Review, April 15, 1999. Reprinted with permission. |

|

Copyright © David Samuel Orr Fund for the Earth. All rights reserved.

|